Editors’ note: What goes into the making of a professional ballet dancer? In this twelve-part series of reminiscences and turning points excerpted from a larger work-in-progress, former Oregon Ballet Theatre principal Gavin Larsen pulls back the curtains and gives us inside glimpses of the challenges, uncertainties, and triumphs of the dancers’ life. Part 4 of “Everyday Ballerina”: Cracking the Door.

*

By GAVIN LARSEN

The next year, the girl, now 10, was moved up into the next level of ballet classes. She’d faked it well enough, copied well enough, worked harder than regular 8- or 9-year olds would, and, unsurprisingly, come to seriously love going to class. The ritual was fun now. Her family, a foursome, escorted her downtown quite early on Saturday mornings, where they all encamped at a table inside Burger King, half a block away from the rattly wooden front doors of the ballet school. They’d get cheese danishes wrapped in airtight plastic bags, or Styrofoam plates of scrambled eggs, sausage, pancakes and maple syrup, and her parents would drink coffee.

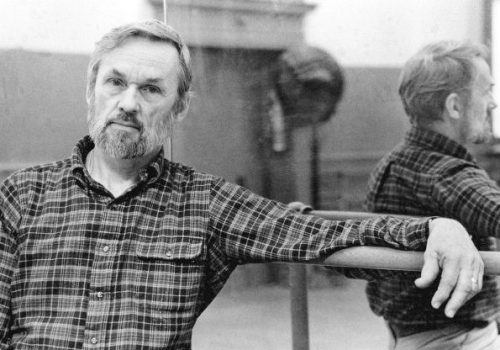

Gavin Larsen

When it was time, she was sent off to walk by herself the half-block to the ballet school, open those front doors, and leave Broadway behind to climb the mountainous flight of stairs. Her parents, pretending to be calm and casual, watched anxiously until she’d crossed the street, passed the candy store, and disappeared through the doors.

The fun of the Saturday morning ritual, though, was only because it was leading up to the dancing-time. And it wasn’t just that the dancing was less terrifying. It was becoming fun. And that was because of the music.

There was a pianist who played for class every week. She was a tall woman, with a puffy halo of tight brown curly hair, who stooped, as if she was ashamed of her height or of herself, or was apologizing for being physically present. But— she was not apologetic musically. When she played the piano, she didn’t hunch. Her music drove, lifted, propelled. It danced, and it probably was her way of dancing, too.

The 10-year-old pinned her spirits on the sight of that pianist-woman slinking in the studio door, always at the very last minute, juggling and dropping binders of sheet music as she murmured apologies and hustled to the piano in the corner.

In the world of professional ballet, practice is an ever-present necessity, and nothing comes easily.

No exercise was hard with music like that. The 10-year-old truly felt the music made her able to hold her leg up higher and longer, and straighter and more proudly. In fact, the music itself was doing the work for her. It took over. Now she had learned some jumping steps, simple ones designed to build strength in the legs and lungs, and the pianist played hornpipes and mazurkas and marches that pushed her, pulled her, carried her along— she could practically see the notes dancing alongside her, teasing her to keep up as fast as they were going, holding her hand as they flew through steps and left muscle burn behind them.

Along with those moments of pure, ecstatic joy, there were still valleys of shadow. The Greek teacher would throw out verbal pop quizzes about the French names of steps and their translation, and ask to see them demonstrated— in reverse. He’d pick a student and ask if they knew who Nijinska was, and if they didn’t, he’d say they had about as much right to be in ballet class as an elephant.

The 10-year-old lived in fear of being called on to answer a question or translate a step she didn’t know. There was no forgiveness for never having been taught or told something. All were expected to know, somehow, whatever the Greek teacher thought they should. Pirouettes had still never been taught to the 10-year-old, but by now she had watched and tried enough times, had learned the position— and held it twice as hard as necessary— to have something of a grasp, though fear still ruled.

Cracks, however, were beginning to show in the Greek teacher’s crusty exterior.

One day, during the summertime, the number of students in class was small, maybe because some had gone off on family vacations, or to sleep-away camp, or weren’t interested enough to keep coming to a musty indoor studio in beautiful weather. The Greek teacher told the class to do a pirouette exercise. By now, the class had advanced enough that many of them were doing double pirouettes, rotating two times around instead of just one. The command on this day was for all doubles, from everyone. Ever timid, the 10-year-old held her breath and her position as hard as she could until it was over.

Come here. The rest of the class cleared to the sides and back of the studio, and the 10-year-old, very nervously, stepped forward.

Do a triple. Having no mechanism to defy her instinct to obey an order, she took the preparation position. And did a triple pirouette.

Now, just for fun and games, do it to the left. So she did.

Somehow, she did.

Richard S. Thomas and his wife, Barbara Fallis, both former leading dancers with George Balanchine’s New York City Ballet, founded the New York School of Ballet in 1958. Among its many students: Twyla Tharp, Cynthia Gregory, Sean Lavery, and, later, the young Gavin Larsen.

*

TOMORROW: The summer of 1992. “I thought I had been duped. I was naive, even for a 17-year-old. But as it became clear that I had failed to notice a huge, crucial, completely obvious basic fact about being a dancer, I was rocked absolutely to the core.”

*

PREVIOUSLY:

Everyday Ballerina 1: Curtain Speech

Everyday Ballerina 2: The 8-Year-Old

Everyday Ballerina 3: The 8-Year-Old, Part 2

*

Born and raised in New York City, Gavin Larsen has been immersed in ballet’s “bizarrely intuitive system” since she was 8 years old and began to study in the same studios where George Balanchine had created some of his finest ballets. She moved on to the School of American Ballet, and a long career performing with Pacific Northwest Ballet, Alberta Ballet, the Suzanne Farrell Ballet, and as a principal dancer with Oregon Ballet Theatre. Since retiring from the stage in 2010, she has taught and written extensively for Dance Magazine, Dance Spirit, Pointe, Oregon ArtsWatch, The Threepenny Review, the literary journal KYSO Flash, and elsewhere.